- Greek and Latin Roots

- ACT Prep

- Presentations

- Assignments

- Things We Discussed

Greek and Latin Roots

Here is the list of Greek and Latin roots for this week:

Here is a link to all of the Greek and Latin roots we have discussed.

Test your memory of the Greek and Latin roots that we have discussed with this quiz.

This is the link to the Wikipedia list of Greek and Latin roots.

ACT Prep

There was no ACT Prep question this week.

Presentations

Tips regarding presentations:

- Try to make your topic more specific

- You have the option of doing other things besides an oral presentation.

- You could do a written project

- You could even write an article for this blog

Assignments

- Fill out the list of Greek and Latin roots.

- Write in the meaning of each root

- Give at least one example of each, be prepared to give its actual definition and the way that it is related to the root word

- Example: If I gave you the root “onym”, you could give the word “synonym” which has the definition of two words with the same meaning. The two roots in the word “syn” and “onym” mean “same name”, indicating two words that name the same thing.

- Fill out the blank space at the bottom with your own root that you have discovered. This will likely come from some of the example words that you have already written. Give a different example than what you have used.

- Example: syn- means “same”, example word “synchronous”

- Be prepared to talk about where you found this information

- Presentation

- Research your topic of choice and be prepared to give a 5 minute presentation on the topic, geared toward people your age level.

- Include the background information needed for someone who does not know the topic as well as you.

- Be prepared to talk about how you found this information.

Next week we will meet on 10/3/24.

Things We Discussed

Greek and Latin roots

Aster

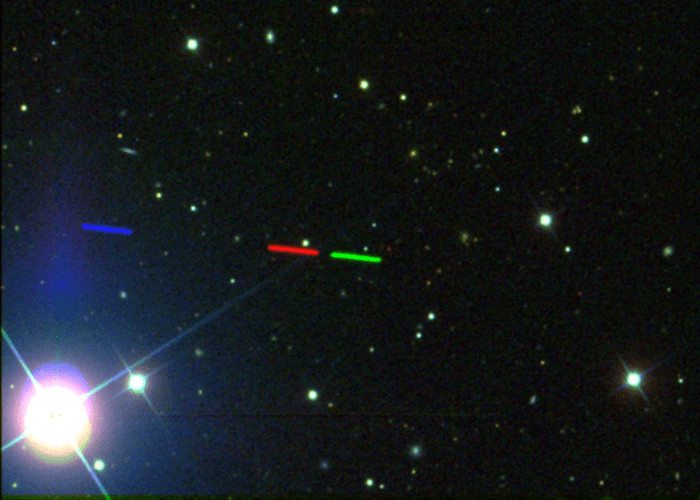

Asteroids

Asterism

There are 88 official constellations. An asterism is a collection of stars that seem to be grouped together but don’t for a constellation.

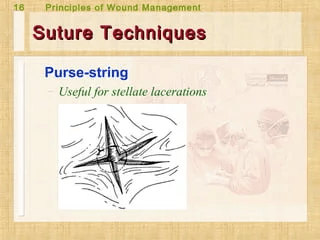

Stellate lacerations

Perijove

This video shows the images taken by the Juno space probe as it goes through the perijove of its orbit around Jupiter.

Perihelion and aphelion

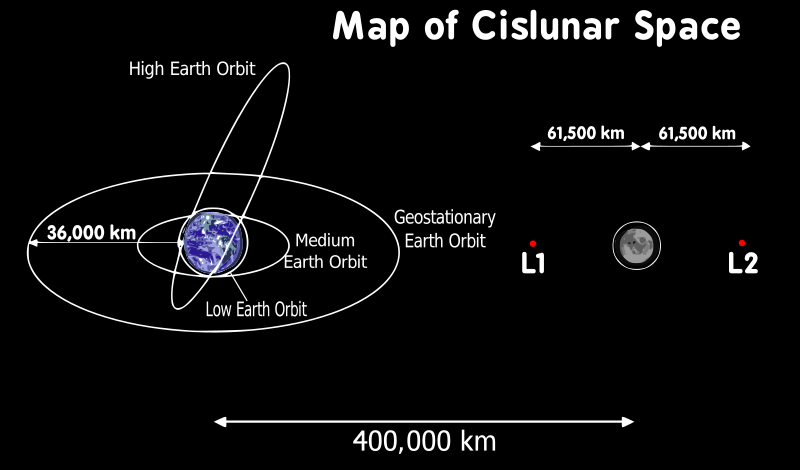

Cislunar

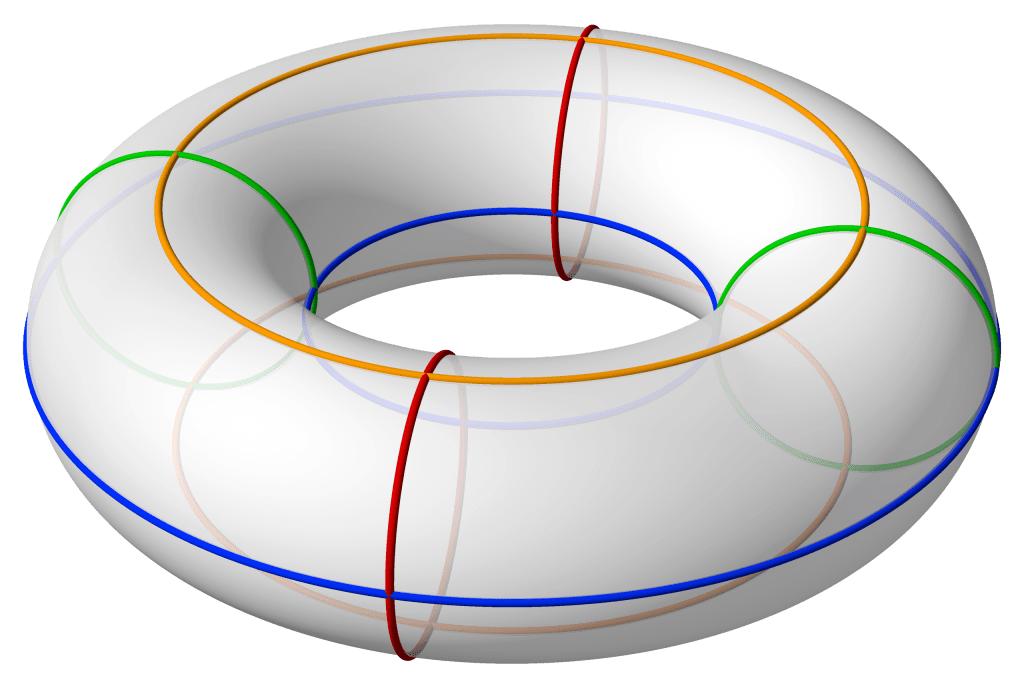

Toroid

Cuboid

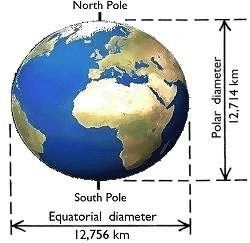

Spheroid

Heliotropism

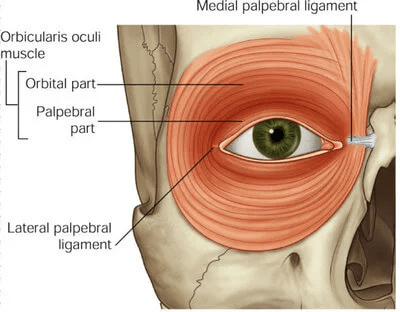

Orbicularis oculi muscle

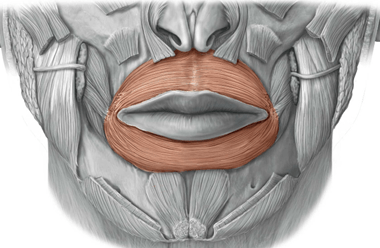

Orbicularis oris muscle

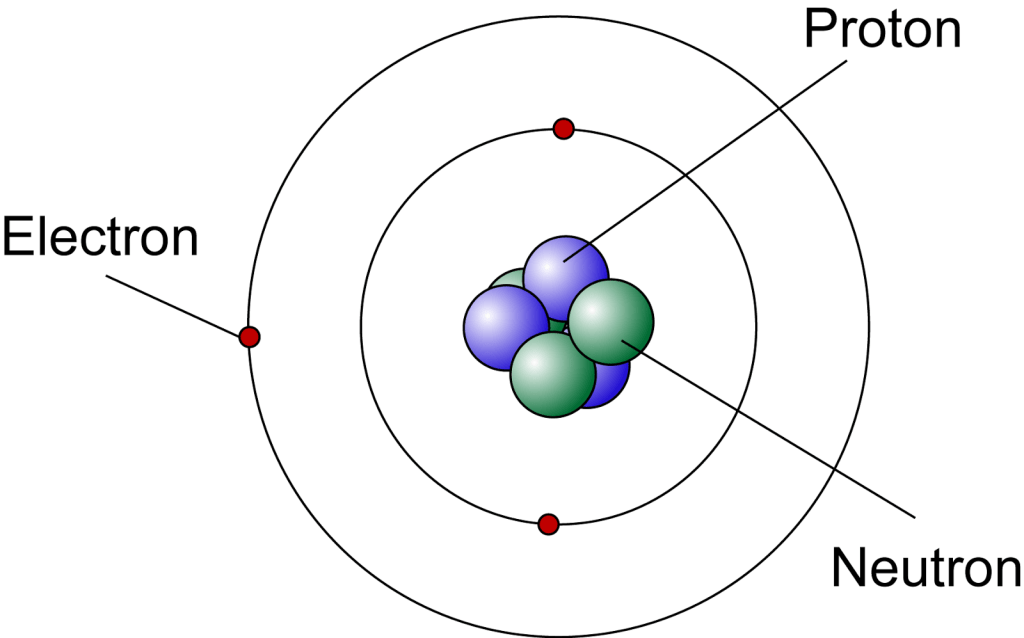

Atoms

Dalton’s atomic theory states:

- Elements are made of extremely small particles called atoms.

- Atoms of a given element are identical in size, mass and other properties; atoms of different elements differ in size, mass and other properties.

- Atoms cannot be subdivided, created or destroyed.

- Atoms of different elements combine in simple whole-number ratios to form chemical compounds.

- In chemical reactions, atoms are combined, separated or rearranged.

Although this was a very useful theory which advanced chemistry significantly, it turns out that many of these points are wrong.

We now know that:

- Atoms of a given element all have the same number of protons, but they can have different number of neutrons. Atoms of the same element with differing numbers of neutrons are called isotopes. Different isotopes of the same element have different masses.

- While it is true that atoms are not created or destroyed in chemical reactions, they can be created and destroyed in nuclear reactions.

- The atoms in large organic molecules combine in ratios that are not simple whole-number ratios.

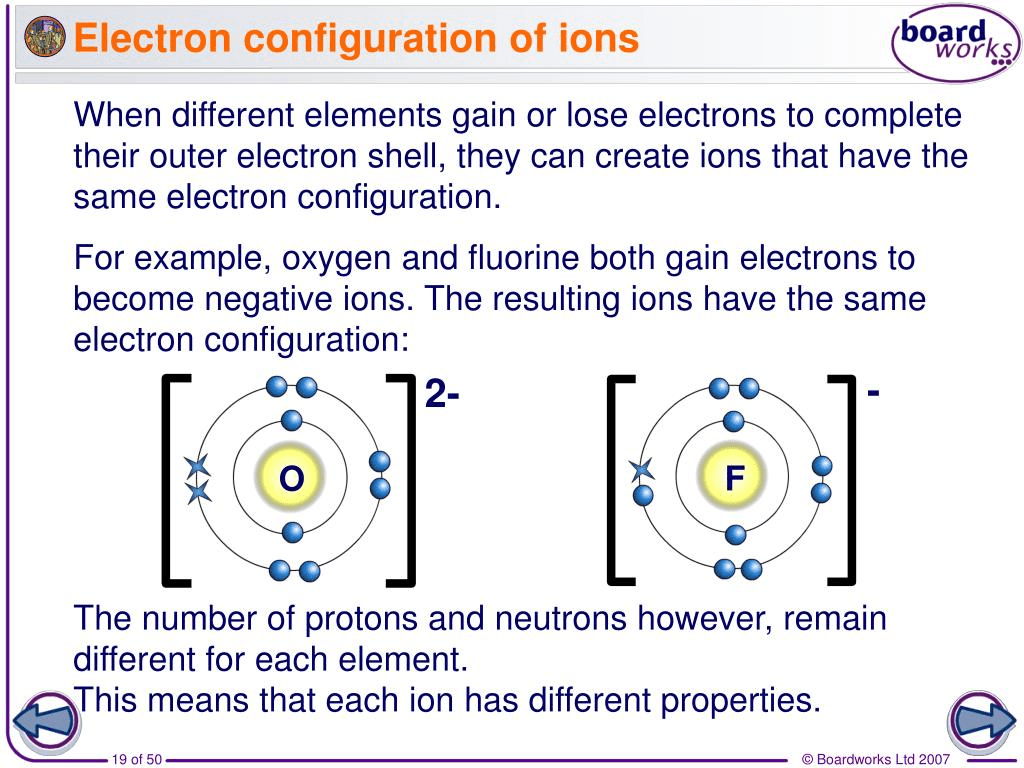

Electron shells

Electrons can be thought of as being organized in shells around the nucleus. (It’s actually more complicated than that.) Each shell can hold a certain number of electrons. For instance, the shell closest to the nucleus can hold only 2 electrons. The next two shells can hold 8 electrons each. The electrons in the outer shell are called “valence electrons”. These are the electrons that interact with the rest of the world and give the atom its properties.

The concept of electron shells explains many aspects of chemistry, including:

- the periodic table

- the way an atom forms an ion

- the number of bonds an atom will form

- the noble gases

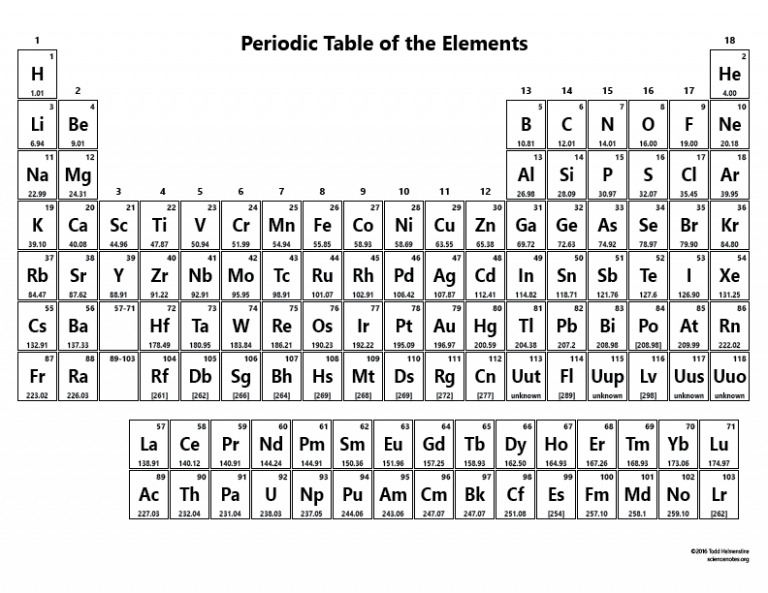

The periodic table

There are only two elements in the top row of the periodic table because the first shell only holds 2 electrons. Similarly, the next two rows each have 8 elements because the next two shells each hold 8 electrons.

Ions

All of the atoms in group I (the far left column) have a single electron in their outer shell. The easiest way for these atoms to have a filled outer shell is to lose that single electron. Losing that electron causes the atom to become a positively charged ion. The atoms in group II have two electrons in their outer shell. They lose both of these electrons to form an ion with a +2 charge.

On the other hand, atoms in group 17 only need one electron to complete their outer shell. They prefer to gain an electron, causing them to form negatively charged ions.

Covalent bonds

The outer shell of carbon has 4 electrons. To complete the shell, carbon would need to gain 4 additional electrons. Or, it could lose the 4 electrons in its outer shell. Either way, this is a big change and so, carbon does not ionize. Instead, it shares electrons with other atoms, and those shared electrons fill the outer shells of both electrons. This is why carbon is good at forming bonds with other carbon atoms, because each carbon atom has 4 electrons to share with other carbon atoms, allowing them both to effectively fill their outer shell with 8 electrons. These bonds are called covalent bonds.

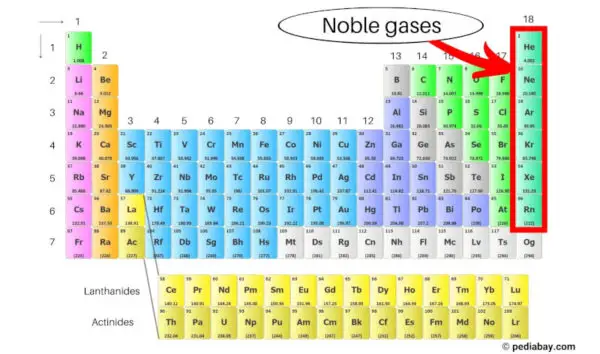

Noble gases

As we move from left to right along the periodic table, the atomic number increases and the outer electron shell gains an additional electron until we reach the noble gases at the far right. The electron shells of the noble gases are completely filled. Because of this, they hold on to their electrons and do not want any others. Therefore, they do not combine with other elements.

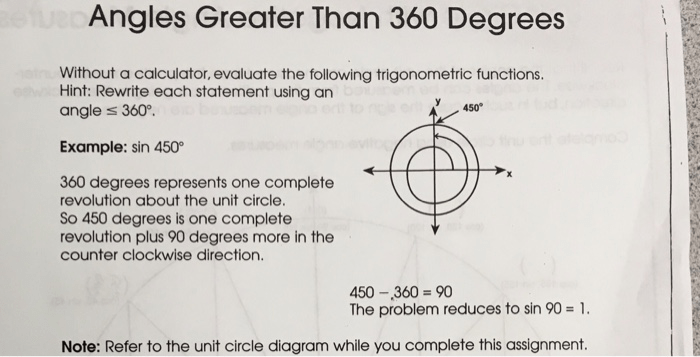

Modular arithmetic

Typically, adding two numbers produces a larger number. However, there are times when numbers have a circular relationship and we actually want the addition of two numbers to yield a smaller number. This is most clearly seen in a clock: 10 + 3 = 1.

Mathematicians have developed a concept called the modulus to work with numbers in this way. The modulus is the remainder after a number is divided by another number. For example above, 10 + 3 = 13, but because there are 12 hours on a clock, 13 mod 12 = 1.

As another example, because there is 360 degrees in a circle, any angle of more than 360 degrees is the same as a smaller angle that is less than 360 degrees. 450 mod 360 = 90

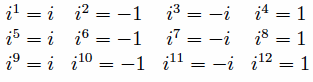

Powers of the imaginary number i can also be dealt with in this way.

10 mod 4 = 2, so i10=i2=-1.

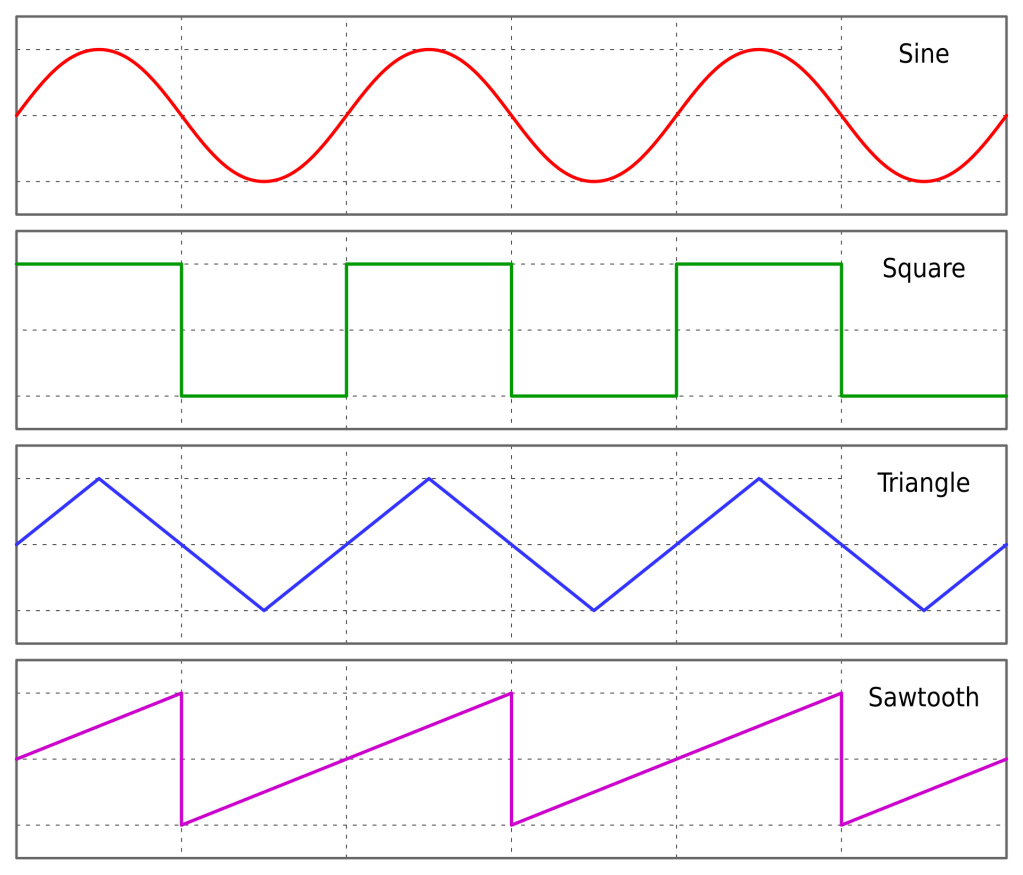

When mod(x,1) is graphed in Desmos, you get this pattern:

Usually, the modulus is only applied to integers, in which case, x mod 1 would always give you 0. However, if the modulus is applied to real numbers, then there is a fractional remainder that gradually increases between integers and then drops to 0 when the next integer is reached. For example, 5.25 mod 1 = 0.25 and 5.75 mod 1 = 0.75.

This is called a sawtooth wave, which can be more easily seen if you imagine drawing a vertical line at each integer, where the plot drops from 1 to 0.

Another interesting function to plot is y = floor(x).

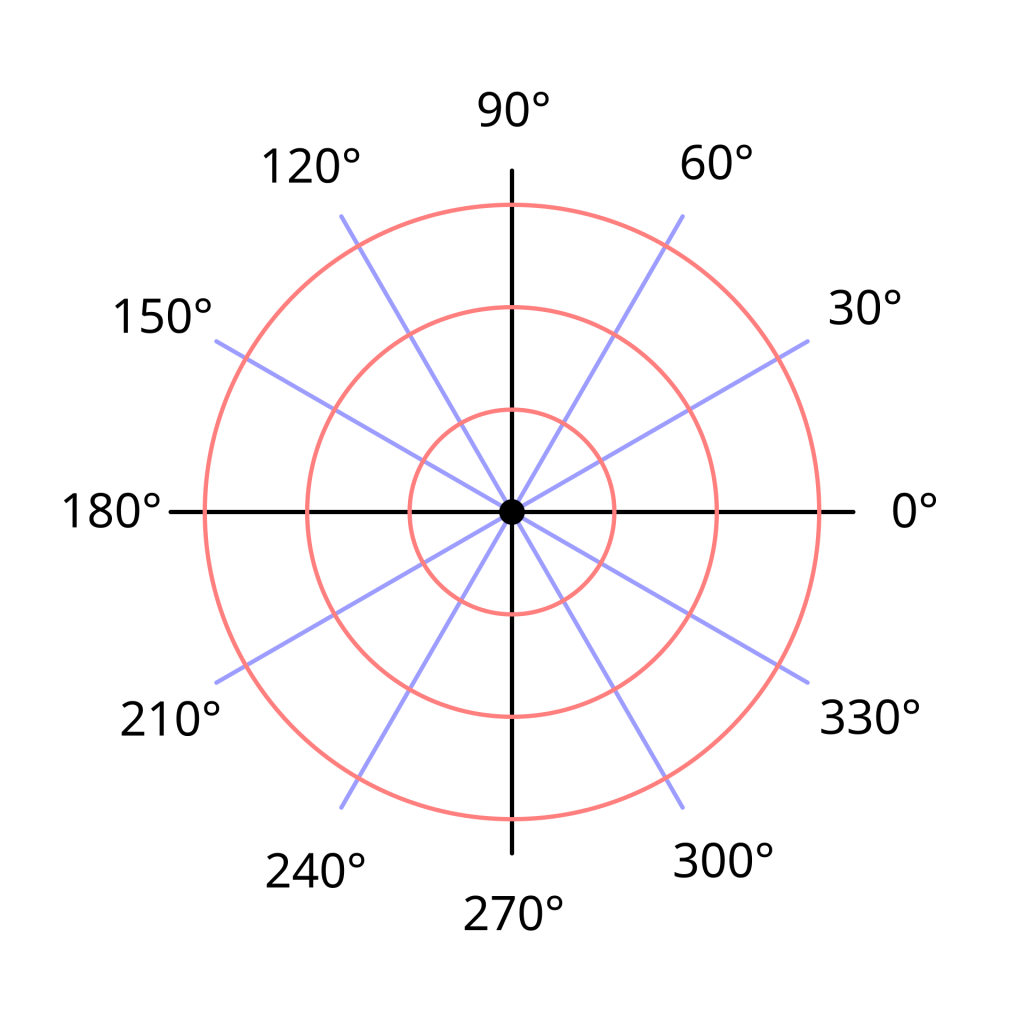

Polar Coordinates

The normal way to graph an equation is to use the Cartesian coordinate system which plots a pair of numbers (x,y) on a rectangular grid.

However, there is another way to plot an equation using polar coordinates. With polar coordinates, the pair of numbers that are plotted represent the distance away from the origin and the angle. The coordinates are usually written as (r,θ), where θ is the Greek letter theta, a common symbol used to represent an angle.

Polar coordinates are best used when all data is measured relative to a specific point, called the origin, such as in a radar system, which measures the distance and angle of an object relative to the radar station.

The equations of some curves become much simpler in polar coordinates. For instance, a circle with a radius of 10 is represented by r = 10 in polar coordinates. But in Cartesian coordinates, a circle is represented by the equation x2 + y2 = 100.

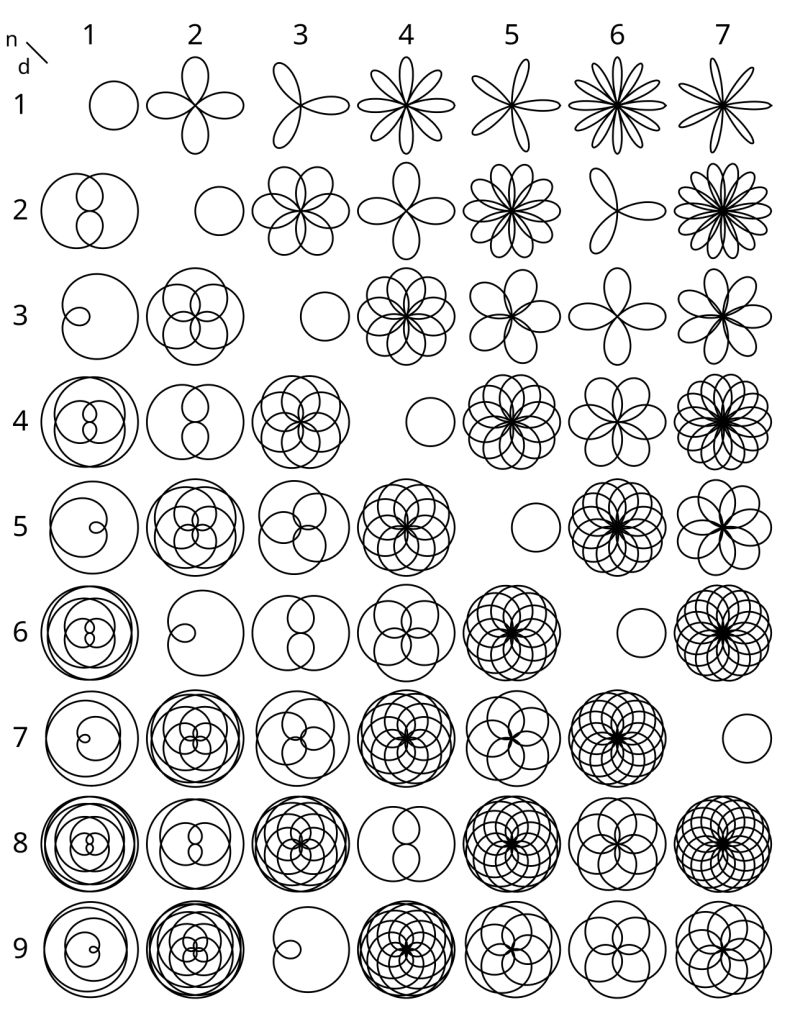

Rose Curves

A rose curve is represented by the equation r = a·sin(nθ) where a is the radius of the curve and n is a rational number.

By adjusting n, many different curves can be obtained:

See this post for further discussion of curves in polar coordinates:

The scientific method

The scientific method involves these steps:

- Observations – a scientist becomes interested in a topic because of something they have observed or by experiments or theories that other scientists have performed.

- Questions – a scientist develops a question based on these observations.

- Hypothesis – a scientist developed an educated guess about the answer to the question.

- Experiment – a scientist performs an experiment to collect data that will support their hypothesis

- Results and Analysis – the results are the actual measurements of the experiment. A scientist will perform an analysis of the results to determine whether the results support their hypothesis

- Conclusions – a scientist will then come to a conclusion about whether the hypothesis is correct or not

- Reporting – reporting the results is essential to the progress of science

Structure of a research paper

Typically, the results of an experiment are reported in a research paper. The structure of the research paper is based on the scientific method.

Usually, a research paper has the following sections:

- Abstract – this is a brief summary of the report, explaining in just a few paragraphs what question the experiment was trying to answer, how the experiment was conducted, what the results were, and what conclusions were made. The abstract helps a reader know whether the research paper has the sort of information they are looking for.

- Introduction – the introduction of the paper usually describes what information is already known about the topic, what motivated the question that is trying to be answered, and what the hypothesis is.

- Materials and methods – this section describes how the experiment was designed and carried out so that other scientists could replicate it.

- Results – this section provides a summary of the data that was collected from the experiment.

- Discussion – this section describes whether the hypothesis was supported by the data, how the results compare to other studies, what the limitations of the experiment were, and what additional experiments might be considered to advance science even further.

Often a research paper will have many authors. These include the “principal investigators” (the head scientists who are in charge of the research) as well as other scientists who collaborate with the PI and graduate or undergraduate students who contributed to the research.

Structure of a review article

A review is written by authors who do not perform research. Instead, they read many research papers and summarize what is known about the topic. In some ways, this is similar to a textbook. However, a review article usually have a very narrow focus and goes in depth about the current understanding of a topic. It often has to deal with incomplete knowledge or conflicting results. A review article is typically more up to date on the state of the art compared to a textbook.

Leave a comment