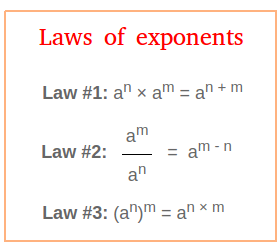

How would you convince someone that Law #1 is true?

a3 = a·a·a

a2 = a·a

a3·a2 = (a·a·a)(a·a) = a5 = a(3+2)

How would you convince someone that Law #2 is true?

A similar argument as above.

How would you convince someone that Law #3 is true?

(a3)2= (a·a·a)(a·a·a) = a6 = a(3·2)

What are the four cases of an exponent not covered by the standard definition for a positive integer exponent?

- a0

- a1

- a-n

- a1/n

The standard definition of an exponent: an = a·a·a…·a (multiplied n times), only applies for positive integers > 1.

However, there are ways to expand the definition of an exponent to make so that they are all consistent with this standard definition.

How would you use these laws to derive the rule for a0?

Law #2: a3/a3 = 1 = a(3-3) = a0

How would you use these laws to derive the rule for a-n?

a-n = a(0-n) = a0/an = 1/an by Law #2

How would you use these laws to convince someone of the rule for a1?

a3 = a·a·a = (a·a)a = a2·a

By Law #1: a3 = a(2+1) = a2·a1

a2·a = a2·a1

So, a1 = a

How would you convince someone of the rule for (a·b)n?

(a·b)3 = (a·b)(a·b)(a·b) = (a·a·a)(b·b·b) = a3b3

This uses the definition of exponents and the commutative and associative properties of multiplication.

How would you convince someone that a1/2 is the square root of a?

Using Law #3: (a1/2)2 = a(1/2·2) = a1 = a

Leave a comment